A war of images

We live in a world of images, more than ever before. That statement is still often heard, but we can doubt its historical correctness.

Images were essential in communication particularly in times when most people could not read and write. So, what happened in the nineteenth century in Europe, when more people than ever before were literate? In fact, in that period, too, images were powerful agencies in a fierce struggle of forms, styles, and class politics as well.

Nowadays we often have the feeling that there is a fierce competition between visual images in a complex world of impressions, on internet, on television, on our mobile phones, along the road, in advertising, and so on. Images can also be potent agencies in conflict situations and can actively trigger people to act, sometimes in a very violent way. This situation of competing images looks like a recent phenomenon. Because of new technological developments we claim a new field of research for anthropologists, and even a certain urgency for this type of research. Naturally, I do not contest this claim, since I do see the importance of research on images and their roles in social-political processes. However, I do not think this is a recent phenomenon.

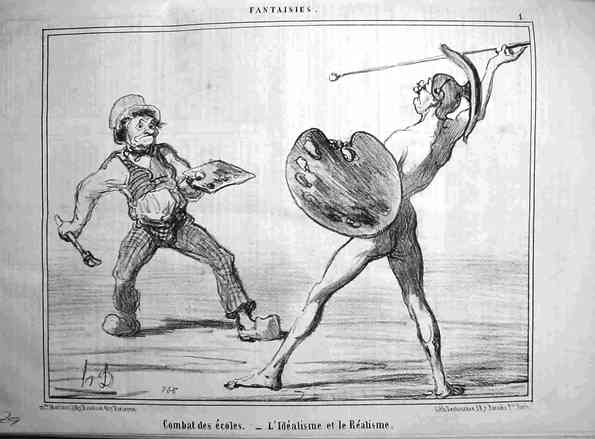

Honoré Daumier published this drawing in 1855. It shows the battle of realism (Courbet) against classicism (David). Clark (1973) convincingly demonstrates that this is also a class struggle between the lower classes and the bourgeoisie.

Images, paintings, prints, and other visual media have always been important, particularly because during most of human history most people could not read or write. Communication through images was essential to explain to the people the norms and values of the dominant religion or the politically powerful elite. In the nineteenth century more people than ever before were able to read and write and the amount of published books and newspapers increased spectacularly. However, this does not mean that images became less important. In the great art-historical controversies of that time, images, and specifically caricatures published in these new newspapers, were powerful weapons in a fierce class struggle. Whether one talks about the reception of the paintings of Gustave Gourbet, around 1850, or the debates around the early work of Édouard Manet, in the 1860s, or the emotional reactions on the impressionist paintings by Monet, Renoir, and Degas in the 1870s, the battles were fought not only in written critical essays, but first and foremost via prints and caricatures. Visual culture was a weapon in a discussion on taste, and therefore a weapon in a struggle for class domination and prompted by a fear of losing privileged positions.

The world of popular imagery was a lively area, and people often recognized the images used, which made the producers of the drawings and the newspapers in which these were published active agents in the field of politics. About the period 1848-1851 T.J. Clark (1973) wrote: ‘Politics would not be fought any longer with official parties, resolutions and books...There began a war of songs, images, ensigns, almanacs; a battle of secret societies which met in the woods; a struggle to suppress newspapers and round up the colporteurs who carried prints and almanacs from village to village;…’ And: ‘Every kind of sign and image was drawn into the struggle. Men were arrested for carrying red flags or white, for wearing the bonnet rouge or the fleur-de-lys, for putting a sprig of thyme in their buttonhole and singing, "Nous planterons le thym, il prendra, la Montaigne fleurira." ’

The point is that fighting by way of images is not new, and that, according to Clark, ‘… art is sometimes historically effective’. The political process in which objects and images ‘work’ is becoming more and more an object of study for anthropologists. This recent interest, however, obscures the fact that these processes are historically very old, and that we may learn a lot from historical and art-historical studies that have addressed these problems before. If we want to see and understand regularities in how images ‘work’ it is not enough to study contemporary processes. The past has offered us plenty of examples and may help us to comprehend what seems so chaotic today.

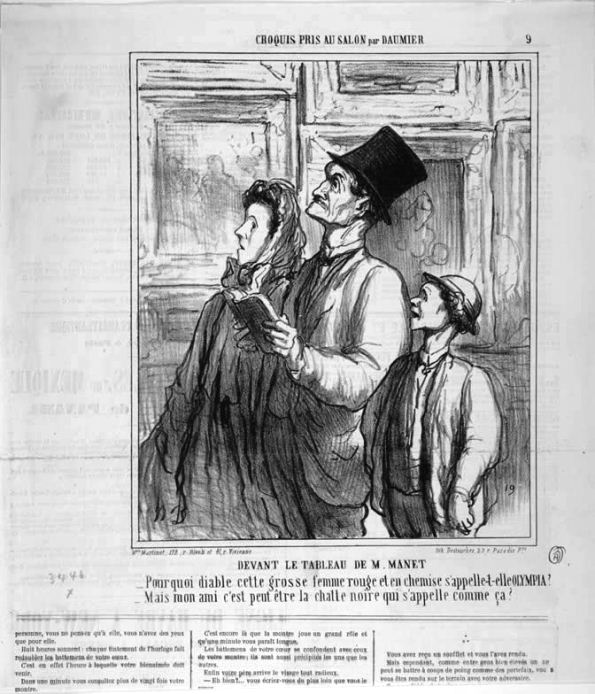

"Looking at the painting of Manet

- Why the devil is this fat, red-faced woman in her nightdress called Olympia?

- But my dear, perhaps that's the name of the black cat."

Honoré Daumier’s comment of Manet’s famous painting Olympia. Sometimes visitors’ reactions towards this painting were violent, attacking it with umbrellas and canes.

For more information on the work of Honoré Daumier, visit The Daumier Register.

0 Comments

Add a comment