Culture: Public or Private?

Looking at the present situation in many countries we have the impression that culture, museums and heritage have always been state financed affairs. Yet, historical reality might offer us a different picture.

Museums to prevent insurrection

Many countries in the world have State financed national museums, based on the European model of the nineteenth century centralized state. These museums all use more or less similar justifications for their existence. In their policy papers they write about educating the people, explaining history and the present-day status-quo.

Unofficially, museum and other types of heritage sites have also been used for reasons of control. Particularly in the nineteenth century European states the fear for a revolt or even a revolution determined to a large extent the national policies concerning museums, collections and heritage. There was certainly an element of control, an attempt to educate the working class, in justifying the existence of national museums. In France this was much stronger than in the Netherlands, but the idea of heritage as a unifying element to prevent schisms in society was certainly important in many European countries.

Dutch reluctance to finance 'troublesome mummies'

The idea of a State controlled heritage politics has been exported to many other countries. We should not think, however, that in Europe the involvement of the State was always, or for centuries, so dominant. In the Netherlands the situation was much more complex, since economic crises and a period of liberal governments in the mid nineteenth century resulted in less government involvement in cultural affairs than, for instance, in France.

While in France Napoleon III deliberately used collections and museums to step in the footsteps of his illustrious uncle, the Netherlands was ruled by liberals who rewrote the constitution limiting the power of the King. The reformer of the constitution, Prime Minister J.R. Thorbecke, had a clear opinion of museums when he was still a Professor at Leiden University, some years before. He wrote a very nasty piece about the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, arguing that it only costs money. He was not impressed by the ‘troublesome’ collection of mummies.

Tiemen Hooiberg (1809-1897)

Privatization and free-lancing as 19th century phenomena

Professor Hans Schneider, one of the former directors of the National Museum of Antiquities, recently presented his new book about Tiemen Hooiberg (1809-1897), a lithographer who worked for the museum. Hooiberg’s long life may be illustrative for the nineteenth century. Although we always saw Hooiberg as a ‘museum man’, as part of the regular staff, it now appears that he was employed by the museum’s first director during the excavations in Voorburg in 1828-1830, as a free-lancer. He was paid according to what he produced and did not receive a fixed salary. He was not badly paid as an independent lithographer, but the museum made him part of the regular staff only in 1861, more than 30 years later.

Hooiberg’s private initiative apparently served him much better in a large part of his life. Only as an old man he profited from changing ideas on museum budgeting by receiving a government salary and becoming a civil servant. Most of his active life he was a private person involved in heritage activities. Nowadays we would call this phenomenon ‘privatization’. Apparently, in the nineteenth century as well, private companies were involved in archaeology and heritage activities.

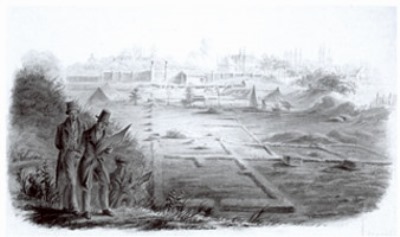

The excavation at Arentsburg (Voorburg), around 1830.

In the middle Caspar Reuvens, halfway down the slope probably Tiemen Hooiberg.

0 Comments

Add a comment