Data confessions of the quantified self

'Quantified Selfers' are people who spend a lot of their time tracking, measuring and counting physical, mental and emotional aspects of their 'selves'. Critics refer to them as narcissistic 'datasexuals'. Dorien Zandbergen offers another explanation.

Sharing the numbers

On 11-12 May of this year I participated in the 'Quantified Self' conference, hosted in the Casa400 hotel in Amsterdam. The term 'Quantified Self' is not generally known outside the circles of attendees. Yet, every person who has ever purposely followed a diet by counting calories, measuring weight, keeping a weight-loss diary, every diabetic trying to balance glucose levels, and every runner keeping track of heartrate during exercise, is already half-way to being a Quantified Selfer.

Halfway, that is, because for most of the conference attendees who do see themselves as a Quantified Selfer, a crucial aspect of their self-tracking activity is the fact that they share their data with others. By sharing these, through presentations at offline gatherings and through online software, they turn the act of self-tracking into a conversational topic. In addition, many self-identified Quantified Selfers don’t confine themselves to 'tracking' only one particular aspect of their activity. Instead, the data-gathering, the tracking, weighing, measuring, counting, and graphing extends to the entire 'self'. The keynote presentations, the 'show & tell' sessions, the 'ignite talks' and the one-hour 'break-out sessions' demonstrated the variety of what this 'self-tracking' could mean.

Logging faces, bodies, moods and dreams

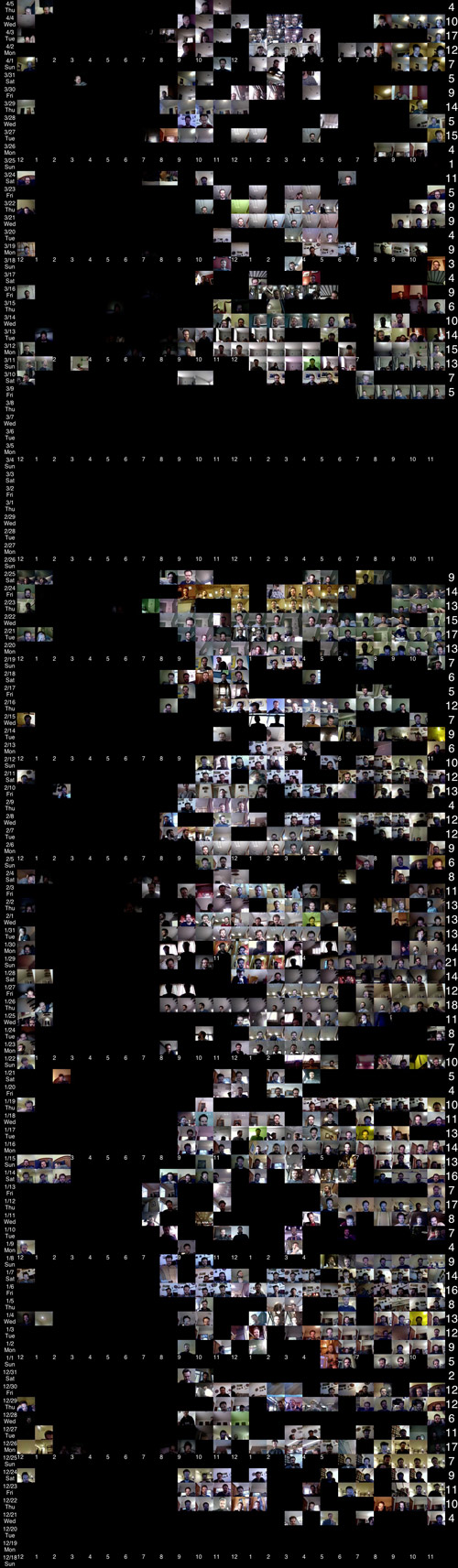

Stan James talked about his program LifeSlize, which took a photo of him every half hour for a whole year with his laptop's camera. Stan tagged the pictures with extra information, asserting whether they were taken in bed or in a coffeeshop; whether it showed only James’s face or him peeking at the screen with another person, or whether he was awake or asleep in front of the laptop. The pictures were ordered and rendered searchable on a timeline, thus presenting him with a visual overview of his 'year in front of the laptop.'

Stan James talked about his program LifeSlize, which took a photo of him every half hour for a whole year with his laptop's camera. Stan tagged the pictures with extra information, asserting whether they were taken in bed or in a coffeeshop; whether it showed only James’s face or him peeking at the screen with another person, or whether he was awake or asleep in front of the laptop. The pictures were ordered and rendered searchable on a timeline, thus presenting him with a visual overview of his 'year in front of the laptop.'

< Stan James's LifeSlize program shown at Amsterdam Quantified Self conference 2013

Nell Watson, CEO of the technology company Poikos, demonstrated how their latest Iphone app FlixFit measures and visualizes her body in 3D. Watson told us how, by tracking changes in body volume throughout the year, the program assisted her in her weight-loss efforts. By tracking changes in body volume throughout the year, the program assisted her in her weight-loss efforts. Robin Barooah and Jon Cousins, who both suffer from depression and stress, presented their 'lifelog' software in which they enter their 'moods' throughout the days. These logs then translate into graphs that visually depict the course of their moods throughout the years, and correlate these moods with other logged life events. Sara Riggare told us how she measures her muscular response time through a program that registers how fast she can tap on the display of her smart phone. Sara correlates this response time to the moments in her day when she takes her medication against Parkinson’s disease. And Luca Mascaro spoke about his app that helps him describe the color, the mood and the narrative of his dreams and to visualize the dreams collected over the years on a graph.

In addition, presenters discussed many other types of gadgets and visualization programs, such as wristbands that measure heartrate and bloodpressure, DNA-sampling tests that graph potential or actual illnesses, and feedback devices that produce a sound when a person appears to be stressed or seems not to have exercised enough.

Datasexual geeks?

Given this focus on quantification, critics have accused Quantified Selfers of being 'datasexuals', i.e., people who have a narcissistic and positivist obsession with the power of numbers. The well-known technocritic Evgeny Morozov writes:

(…) one hidden hope behind self-tracking is that numbers might eventually reveal some deeper inner truth about who we really are, what we really want, and where we really ought to be. The movement’s fundamental assumption is that the numbers can reveal a core and stable self-if only we get the technology right. (Morozov 2013: 232)

Seen in this light, the QS movement is yet another instantiation of Silicon Valley geekhood, with people trying to translate even those ambiguous and emotional experiences of everyday life into objective numbers.

Indeed, for some Quantified Selvers, their love for quantification is married to a distrust of the 'easy-to-manipulate' human brain. As QS aficionado Greg Beato writes:

instead of thinking with our flightly, emotional, easy-to-manipulate brains, we’ll be feeling with our rational, measurable, hard-to-manipulate guts

![]()

Jon Cousin's Moodscope graph, shown at Amsterdam Quantified Self conference 2013

Language for self-disclosure

Yet, when we try to explain ethnographically the diverse motivations and experiences that shape the burgeoning group of people who define themselves as 'Quantified Selfers', and to situate this group in the historical and present context of todays global information society, such characterizations of data positivism only bring us halfway. As a matter of fact, critics of QS who focus solely on the alleged 'love of numbers' show a tinge of positivism themselves: they disregard the forms of interaction and the types of conversation that occur within this 'community' around the act of data production.

At the conference, I not only saw a community 'in love' with numbers, but also people engaging in radical acts of self-disclosure. Standing on stage they talked about painful episodes in their lives (depression, anxiety); they showed their bodies virtually (in every sense of the word) naked; they showed their dreams, their diary entries and their meditation practices, and they talked about their physical diseases and their struggles against overweight. In addition to a bunch of rational geeks, then, I also saw a confessional community for whom these numbers did not merely refer to some hidden objective truth of life. Instead, these numbers seemed to constitute a language for communicating experiences that are difficult to convey otherwise.

Some QSers strive for self-improvement and 'optimization' of their bodies and minds by relying on the alleged objectivity of numbers. Yet, as also observed by Whitney Erin Boesel, another anthropologist present at the conference, many other QSers value the act of data production and sharing in and of itself as an act of 'mindfulness' and as a form of communication. In other words, the 'data' produced by QS gadgets, are valued not only in terms of their objectivity but also because they are part of a community-forming language. This community constitutes its world as much through a faith in objective science as it does through attempts to address emotional, sensory and mystical experiences in a global society that increasingly speaks 'data'.

For more informtation visit Dorien Zandbergen's research blog 'The Last Resort'

0 Comments

Add a comment