Loneliness in solidarity and solidarity in loneliness - How students in Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology navigate the Covid-19 crisis

Essays of 68 CADS students show their struggle with the effects of the Covid-19 measures. This blog reveals how students navigate the crisis and, in light of a recent Monitor on student mental wellbeing, calls for more qualitative inquiry into underlying issues in order to find solutions.

Early on in the Covid-19 pandemic, Leiden anthropologists analyzed its social effects and reflected on the new questions it raised about living together. Now, 1,5 years later, we aim to provide a glimpse of what this means for a group that are being hard-hit by Covid-restrictions, but whose voices are only beginning to get heard. Inspired by the richness, frankness and importance of students' experiences, this blog reflects on key themes that emerged from the sociological essays of 68 first-year and minor CADS students.*

While the aim of the essays was for students to practice using key sociological concepts to analyze everyday situations, they turned out to reveal a lot about students’ current struggles as well as the ways in which they navigate these. Their reflections echo the results of a recent and first-of-its-kind Monitor on the mental wellbeing of students in the Netherlands. This study, which is based on a sample of over 28,400 respondents, shows that feelings of loneliness and stress are experienced at various levels by as many as 80% and 62% of students respectively. It also shows that, while these issues pre-date Covid, their prevalence has increased during the crisis, mainly as a result of the imposed restrictions.

Disconnect

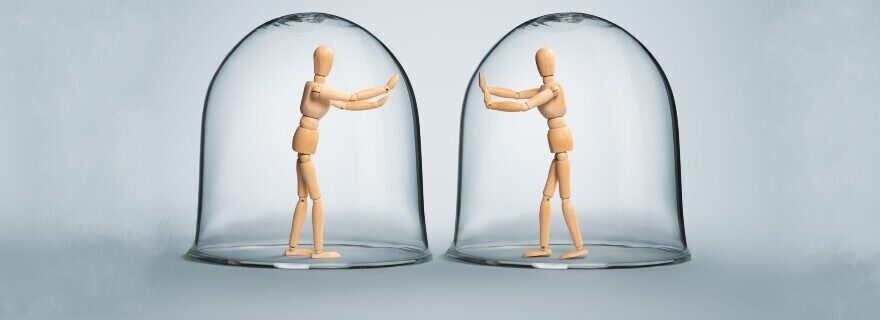

Many of the students’ essays focused on how Covid-restrictions have limited their opportunities to interact with family, friends and peers, which often led them to experience increased feelings of loneliness. The sense of isolation appears to take the most extreme form among international students who only recently arrived in the Netherlands. As one of them gradually began to realize, ‘the perception of oneself starts in the encounter with the other’ and when such interaction is lacking, one risks losing the sense of self. Being abruptly taken out of their regular social lives hindered the students in dealing with personal issues in a stage of life during which their social networks are tremendously important. One of them noted: ‘as the world of young adults narrowed, they longed for interactions with their friends.’

Especially life events that were already highly impactful in pre-pandemic times became harder to deal with during the repeated lockdowns. One student described how the emotional impact of the passing of loved ones was intensified by limited possibilities to say goodbye and go through collective rituals that mark death and mourning. In isolation, the students are alone with their emotions, with little to no opportunity to call upon their network of support, be it their family, friends or mental healthcare professionals.

From other essays, we gather that the students specifically missed their grandparents, whom they could not see for a significant portion of the pandemic due to the government rules. Although many stated that the restriction worked to protect their grandparents’ physical wellbeing, they also emphasized how it compromised mental wellbeing, and how their worries about their grandparents were left unaddressed. This led some to question if the costs of Covid-regulations are being taken seriously enough. Several of them have highlighted that while such efforts were made in an act of care and solidarity, in doing so, a counterproductive situation was created where the young and the old felt disconnected from each other and the rest of the world.

Togetherness

On the other hand, many essays also shed light on more positive experiences. The introduction of a total lockdown for example, became a window of opportunity for some students to experience and reflect upon self-development, the growth of friendship and family bonding, generated by, as one student phrased it, having "extra" time’. Another student similarly underscored this and argued that being forced to restrict daily activities made him re-value fundamental bonds and relationships that he took for granted in the rush of life before Covid. Taking this even further, yet another student showed how precisely that rush never suited her personality anyway, emphasizing how the diminishing social obligations gave her peace of mind.

Moreover, numerous students expressed that the restrictions amplified a feeling of ‘we are in this together’, which in turn attenuated the sense of loneliness and alienation. To illustrate this, one student reflected on how the limitations on the number of visitors one could host strengthened existing friendships. By collectively making decisions on how many guests they felt comfortable welcoming, she and her housemates were brought closer together. As another student concluded, the restrictions shaped ways of interaction in such a way that ‘[the students] felt connected to each other even though [they] were not able to meet in person, and [they] knew [they] were not alone’. These observations resonate with the above-mentioned survey findings that when young adults receive social support from family and friends, feelings of loneliness and stress are considerably mellowed. Thus, new and old forms of solidarity can significantly help in navigating loneliness.

The limits of resilience

To say we are in an unprecedented (mental) health crisis would be an understatement because students already encounter loneliness, anxiety and stressful situations without the pandemic. But as the CADS students conveyed in their essays, such feelings can be eased by showing and receiving a sense of solidarity to and from those who are around us. Many of the essays demonstrated students’ flexibility, whilst also highlighting the limits to their resilience. This is where we as anthropologists would like to argue that a qualitative enquiry on the subject would be meaningful, as the thick data that it generates can complement more quantitative surveys and will allow us to uncover what is implied in the students’ concerns. We can then hopefully start thinking of ways to address underlying issues and identify possible solutions; solutions that are, as expressed in the students’ essays, desperately needed.

*Out of 167 students who wrote a 450-word essay for the course Diversity and Development in Sociological Perspective, 68 students gave consent for their essays to be included in this blog-post. Of these, 55 students also wished to be co-author. Their names appear here along with the names of the teachers involved in the course and this blog-post: Tom Legierse, Anna Notsu, Marit Hiemstra, Willem van Wijk, Giada Avi, Veerle Berk, Maxine Bourez, Brendan Casteleins, Dominique Cents, Luise Christian, Julia van Diepen, Pippilotta de Galan, Divya Goelzar, Julia Gorzelańczyk, Lila van Grieken, Hylkje Heeres, Henk Hendriks, Sasha van Hoorn, Tsz Yau Hui, Daria Ilina, Eva Koet, Jette Koops, Max Kuitems, Naomi Lawson, Carola Levi, Hannah Lhotka, Chaeyeon Lim, Angelica Lima, Dara Looij, Paula Magunna, Benjamin Maldonado Fernandez, Agnieszka Marcinkowska, Isis van Melzen, Tosia Milewska, Sara Nunes Braz, Weronika Ostapiuk, Merle Overmeire, Viola Palmiotto, Thalia Pinidis, Katja Poelwijk, Marit Postma, Ambika Ramachandran, Jeanine Ros, Marieke Ruitenberg, Masaru Saito, Summer Schoen, Hanna Schoneveld, Jeroen Schreuder, Sophie Spickenbom, Maarten Spits, Sabine Spriensma, Helene Stiesmark, Noela Streifeneder, Demi Stroober, Luna Vaupel, Laura van der Werf, Xu Yang, Sibley Zepeda, Holly Zijderveld and Tessa Minter.

0 Comments

Add a comment