New Moroccan cinema reflects diversity in society

Until March 19th, EYE shows the work of contemporary Moroccan film makers. They present non-exotic and diverse images of their own society; fictitious stories that contain cutting-edge social analyses.

Not the tourist office

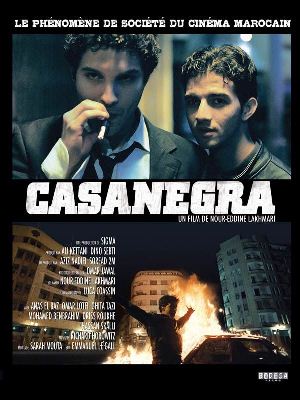

'If you are expecting camels and sand dunes, this film is not for you…' That is how Nourredine Lakhmari introduced his film Casanegra. ‘I am a film maker, not the tourist office; I want to show the darker reality of contemporary Morocco.’

Casanegra, set in Casablanca, was the third film in a series of seven films by young and mature Moroccan directors that show, according to the website of the EYE Film Institute Netherlands, 'a turbulent present – marked as it is by fast means of communication and political and social upheavals – in confrontation with traditional Moroccan society and its age-old customs.’

Casanegra by Nourredine Lakhmari (2008)

Such an announcement for a film programme, which reads like an anthropology conference, triggered my imagination. How would these film makers blend fiction with non-fiction?

The programme has been compiled by writer and scholar Fouad Laroui. From Moroccan origin himself, Laroui is a contemporary Renaissance person in my opinion, with academic as well as artistic output across borders and languages. A selection done from his perspective gets filtered through the finest possible mesh.

Neorealistic elements

Although Nourredine Lakhmari himself has said he uses film noir as a genre ‘to show the darker reality of contemporary Morocco’ I could not help but detect a fair amount of neorealism in the films I had seen. All three directors, including Mohamed Abderrahman Tazi in Badis and Ahmed El Maanouni in Les coeurs brûlés, had applied on-location photography, and some worked with non-professional actors and/or extras. These are typical neorealist elements.

Badis by Mohamed Abderrahman Tazi (1988).

Furthermore, the stories and dialogues turned out to be directly related to real lives as well. We discovered this after the screenings, during the sessions when Laroui enters into conversation with the directors and the audience. These glimpses behind the scenes relate the reel to the real: to what extent do the stories ‘represent’ real lives?

Constructions of authenticity through stylistic means, providing a documentary feel, appeared for the first time with the cinematic and political movement of neorealists in Italy after WWII. Film makers such as Rossellini, De Sica and Visconti took cameras out into the streets amongst ‘ordinary’ people for the first time, revolting against bourgeois stories told from inside film studios. Is it a coincidence that contemporary Moroccan film directors use elements from this cinema tradition? Maybe not.

Les coeurs brûlés by Ahmed El Maanouni (2007)

Art and social analysis

One thing they revolt against is exotic images of Morocco, made by foreign film directors, using landscape and clichés as backdrop for their own stories that have little or nothing to do with Morocco itself. Yet, as Nourredine Lakhmari claims, ‘Morocco is an interesting place and should not be reduced to a picture postcard! It is a mix of Berber, Jew, Andalusian, Portuguese, and French influences on the crossroads of Europe, Arab countries and Africa.’

However, Lakhmari is concerned not only with outsiders’ perspectives on his country: ‘We need to show our own society the darker truths and dare to speak about the unspoken - the non-dit in French – and learn to accept who we are and what our problems are; then move on!’

In Casanegra you get immersed into the lives of two unemployed young men in their early twenties – in sociological terms representing a huge part of society. Their day-to-day ingenious, witty, yet painful struggle for survival takes you through a rollercoaster of ups and downs until you discover the catch-22 they are in. You feel ready to swim to Lampedusa yourself. No academic or journalistic writing has ever had that effect on me, only literature can play the same trick. Great what art can do.

But in my view Casanegra is social analysis, too, as it shows for instance the complex workings of corruption and criminal behaviour. Even the most kindhearted character will in the end become corrupted by grim socioeconomic circumstances, the film seems to say. It criticizes society, shedding light on the underprivileged - like Italian neorealists did in their time.

Open artistic climate

Apparently the working climate for directors in Morocco is such that these rather critical films can indeed get made. However, not all stories deal with the lower classes, nor do all films contain neorealistic elements. I just returned from the fourth film in this series, which did the complete opposite: Rock the Casbah (2013) by Laila Marrakchi.

Les coeurs brûlés by Ahmed El Maanouni (2007)

This film is situated around an exotic Garden of Eden near Tangiers, with sunshine throughout. Its main characters clearly belong to the top of the Moroccan upper classes, including a live-in maid as second mother. No film noir here but rather Woody Allen’s Hannah and her Sisters as cinematic point of reference.

Yet, underneath an easily digestable universal story about death and family secrets, Marrakchi unveils almost in passing the underprivileged position of women in Moroccan society. She rocks the boat carefully: Whenever things get too sensitive, she has her cast turn a corner. Until they try liberties again, in the safety of actual sisterhood - a freedom they dare experiment with only now that their controlling father has died.

The film may have a happy end, yet it is precisely here where Marrakchi has hidden the highly controversial issue of unequal inheritance laws, favoring men. An issue still too much of a taboo to tackle in Moroccan politics can apparently surface in the arts, as long as it is treated with a light, playful touch.

More windows on the world?

Two more films to go in this series and the audience is growing by the week. That is good news for films that do not get distributed in the film theaters or shown on television otherwise. What windows on the world are we missing out on? Could there be more interesting ‘non-Western’ cinema lurking somewhere? Would there be more Larouis that could introduce us to equally well-balanced cross-cuts of contemporary cinema from elsewhere, laying bare great diversity in terms of style, content, gender, class, etc.?

Such films pinch holes in our monolithic stereotypical worldviews. No wonder that my anthropologist/film maker heart gets overexcited…

The films are screened at the EYE Film Institute Netherlands every Wednesday at 16:15. Each screening is followed by an interview with the director by a prominent guest:

- March 5th: Les cheveaux de Dieu - Nabil Ayouch (2012)

- March 12th: Mille Mois- Faouzi Bensaïdi (2003)

-

March 19th: La vida perra de Juanita Narboni - Farida Benlyazid (2005)

0 Comments

Add a comment