The Future as a Humanist Ideology

On the 26th and 27th of June an international conference in Leiden brought together critical insights into “The Future” as a humanist ideal. The desire for a better, more peaceful and more plentiful life for all humans may not be as innocent as it seems.

Unrealistic assumptions of a humanist future

Modern people have long liked to think of themselves as capable of making the future, of constructing, from a universe of unlimited possibilities and natural resources, a better, more peaceful and more plentiful human life. But what if this humanist future, whether based on secular utopias or on rational prognosis and calculation, turns out to be based on cultural assumptions that hide the violence, exclusions and dehumanization that are required for its realization? This was the main question that arose from the international conference on ‘Futurities’ (or forms of the future).

The conference was organized by the NWO-sponsored research project “The Future is Elsewhere” of the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology in collaboration with Duke University’s Franklin Humanities Centre. Twenty presentations covering a global range of cultural practices identified the future as an essential assumption of humanism, and explored possible alternatives. The discussions, summarized below, produced a first outline of how necessary critiques of such humanist assumptions are.

Neo-liberalism and the time of the commodity

Our present future is often imagined as the neoliberal triumph of the market, but we tend to forget that neoliberalism first entered politics by Pinochet’s coup in Chile in 1973, and Thatcher’s subsequent destruction of the British miners’ unions. Violent ruptures also characterize neoliberal futures in more modest and less physical ways. Introducing commercial insurance to South Africa’s poor not only involves bounding them off as a market segment, but also needs to scare them into buying an insurance policy. Startup companies in Singapore may think of their product as “making a dent in the universe” (as Steve Jobs once said), but see themselves turned into commodities by the logic of investment.

Whether a Colombian town needs to be removed to gain access to gold deposits, or the pain of a neoliberal coup has to be denied to ‘brand’ Chile as a nation at the Shanghai World Expo, such examples confirm that the future of the commodity is based on a rupture with the past of its production. When commodified as a desirable object, the humanist future threatens to classify a “we” that excludes others: the alternative histories involved in its real-time production. However, presentations on popular Islamic music and science fantasy film and literature showed that commercial channels are also used to reinforce and reinvent alternatives and contest the hegemony of neoliberal ideology.

The eternal return of epochal change

Therefore, whereas many feel that, since the triumph of neoliberalism, we have entered a “new” era of financial commodities and digital simulacra, the clean break that such notions of epochal change assume seems a modernist self-conception that often hides different, even duplicitous futures. Long before neoliberalism made its mark, the endless repetition of development schemes in Mozambique that declared its beneficiaries to be “not yet” in the future, or the repeated prediction of the extinction of indigenous peoples in Indonesia since the nineteenth century, show that the “new” of modernist futurism tends to return time and again.

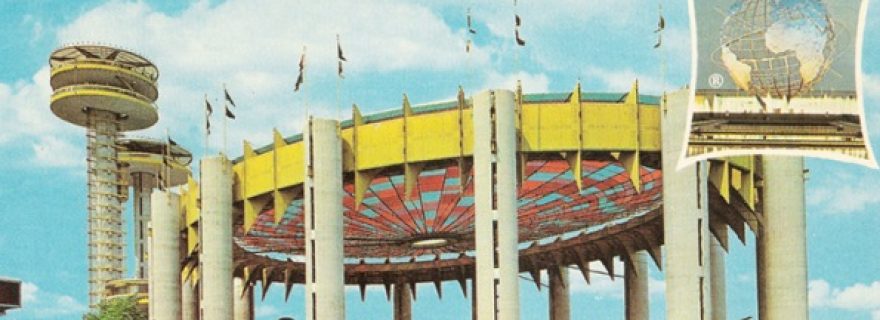

It can do so because it fetishizes the old and the new - for example, by ignoring that modern world exhibitions since 1851 were as much preoccupied with producing individual experience through simulacra as so-called ‘postmodern’ ones; or by forgetting that for Malaysian sailors, the future still comes from another part of the world. It often pushes alternative futures into more marginal temporal or spatial enclaves – a ‘parallel’ social world where Vancouver drug addicts are more safe from harm; a ‘processual time’ where alterglobalists experiment behind the public scene of protest with more democratic alternatives; an indigenous reservation in Indonesia where sustainable forest management can be rewarded. This belies the humanist assumption that the future is publicly accessible to all.

Temporal classification and the future in fragments

This is not to deny change: the future is, indeed, no longer what it used to be. Instead, we should recognize – as Stewart and Harding did when analyzing the rise of apocalyptic futures in the USA since 1980 – that the public and universal future of secular humanism has fragmented into one enclave among others. The promise of human improvement is not dead – even if we suspect that “the future” may become a classification that excludes others (whether in terms of “democracy” or “the market”), human beings still need faith in what they do, and the hope that they can do better. But it may only be maintained once we accept an inescapable ambiguity: that the humanist classification of the future as open has often worked to close it down for others – just as the future of “asylum” in a modern nation-state has denoted political hospitality in terms of rights as well as incarcerated those rejected in terms of gender and race.

The presentations showed that such examples can be multiplied: they questioned whether “Europe” does, indeed provide a future for all inhabitants of a new member state like Latvia; whether thinking the future from within the body – a body that ages, but also considers the future for its children – does not force us to consider decay and entropy as partially non-human alternatives; or whether the black consciousness of someone like Aime Césaire does not produce an alternative public sphere where the historical tie between humanism and nation-state sovereignty is unmasked as a secular theology based in slavery and colonial rule. It seems that this multiplicity of temporalities should be our future concern.

Disciplinarity, methodology and language

However, this requires much further work and discussion. The conference’s interdisciplinary engagements between philosophical and sociocultural anthropology, literary studies and history faced disciplinary hegemonies – especially entrenched in some forms of economics, political science or sociology - that have appropriated the humanist future. We are in need of a methodology that challenges such appropriations and reveals the temporal assumptions many of our methods hide.

Another challenge is the modernist call for “innovation” that resonates in academic Europe, and that reduces even humanism to narrow technological and utilitarian ‘improvements’. Many presenters also voiced a need for exploring the cross-cultural vocabulary in which we can speak of the future – not just because the everyday grammar of le futur seems to differ significantly from reified conceptions of l’avenir (to mention only one example), but also (to mention another) because even prophetic futures seem less apocalyptic when we compare Islamic to Christian millenarianism. We can predict, then, that the conference will produce equally successful follow-ups in its own future.

After the international conference on Futurities our group was invited on a boat tour through the canals of the city of Leiden. A lovely end of an interesting and succesful conference.

0 Comments

Add a comment