14.8%

Before the millenium the Netherlands had one of the lowest percentages of female full professors in the world. What has changed since then and what does it tell us about gender equality in academia?

Research on gender equality in academia

I vividly remember learning in my anthropology of gender class that the Netherlands had one of the lowest percentages of female full professors (in Dutch: hoogleraar) in the world. Even if I don’t remember the exact statistics, I still remember the low global rank—maybe because our professor added, not exactly politically correct, that the Netherlands were “ranked slightly below Botswana.”

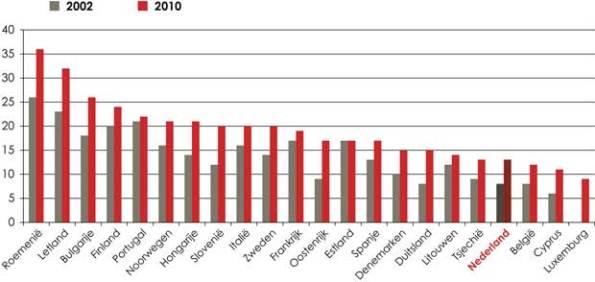

That was in 1995. Almost twenty years later, I am now an early-career anthropology professor ('docent', so not a full professor) at Leiden University, where I recently had the pleasure of leading a workshop on gender as part of the symposium “Excellence through Diversity”. Not surprisingly, the male/female ratio among full professors came up here, too. With only 14.8% of full professors in Dutch universities being female, the Netherlands ranks among the bottom of European countries in terms of gender equality in the academy—only slightly above Belgium.

Stichting de Beauvoir, WiS database (DG Research, EC), preliminary She Figures 2012.

The issue of gender equality in academia is not just about academic jobs either. Inequalities also exist in the factors that are needed to secure academic positions, such as publications, grants, and administrative experience. Female academics appear to be at a disadvantage in sometimes unexpected ways, such as documented in a recent study on the 'Gender Citation Gap', which found that in the field of political science female-authored papers were systematically cited less than male-authored ones, all else being equal.

Obviously, the symposium at Leiden did not magically solve what is clearly a multi-faceted problem, but it did mark an important renewed commitment from the University to addressing some of the issues involved, for example through the appointment of a diversity officer.

Visual representations of gender

The gender workshop offered as part of the Diversity Symposium was built around visual representations of gender, and aimed at giving students and other interested participants a clearer sense of what gender means and how and where it matters. A video on gender mainstreaming from a Swedish organization devoted to helping local governments become more gender-conscious, shows the surprising ways in which gender plays out in people’s everyday lives—for example, when it snows.

As it turned out, snowy conditions in Sweden adversely impacted women, who were more likely than men to be pedestrians and cyclists, and travelling on roads with a lower priority for snow removal. When local governments started looking at injury statistics, it became apparent that more women than men suffered snow-related injuries. The issue was remedied when the government changed its priority areas for snow removal. This simple example reminds us that gender can matter in unexpected ways, even if the model of how gender imbalances could be fixed, does not provide a straightforward metaphor for solving gender inequality in the context of academia.

The second visual representation of gender presented at the workshop was the ‘genderbread person’. Where the Swedish video maintains an easy distinction between 'women' and 'men' in order to highlight their different needs, the genderbread person is more reflective of gender scholarship, which focuses on the flexibility of gender roles and the frequently unclear boundaries between men and women.

We also learn from this figure that the different dimensions associated with gender—for example, its biological basis, its external expression, or people’s own sense of who they are—are not necessarily correlated. This makes for a much more complicated picture than the common-sense assumption of a world made up of men and women. Scholarship on gender continues to evolve, as evidenced by the fact that the original genderbread person has been reworked as genderbread person version 2.0.

Lower female participation in the Netherlands

The workshop was concluded by some clips from the film 'Mevrouw de Professor' (Ms. Professor) commissioned by the Dutch Network of Women Professors. Coming back to the issue of the low percentage of female full professors in the Netherlands, the film does a nice job debunking some of the spurious explanations commonly adduced to explain lower female participation at the highest academic level.

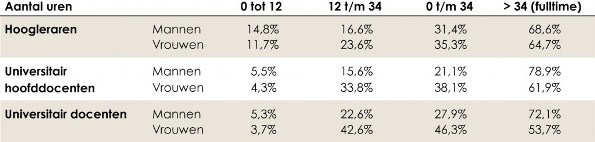

Is it because women are less smart than men? No. Is it because too many women work part-time and/or take too much time off to care for the kids? Not quite. Here, too, the picture is more complex than commonly assumed, with more women in the Netherlands working full-time in academic jobs than in other sectors, for example.

Stichting de Beauvoir, VSNU, WOPI, ultimo 2011, in fte 2, exclusief wetenschapsgebied Gezondheid.

As these examples show, it’s not women who are the problem. The Vice-Rector Magnificus of Leiden University, Simone Buitendijk, put it very well at the symposium: it’s not about individuals changing their personalities—it’s about changing the institution.

3 Comments

Very important issue. Thanks for sharing your report. Two complements to your excellent points: (1) It's impt. to look at gender across faculties, and then correlate this ratio to their budgets. I observe that faculties/occupations with more women (i.e. Arts, Anthro) tend to be the first cut when public budgets are crunched. Indicates how women's interests, skills, and experiences are devalued and underrepresented by leadership power structures. (2) The ratio of women as master students compared to women as PhD, docent and hoogelelaar is extremely impt to monitor. When the numbers significantly shrink going up the value chain, and is especially disproportionate between MA and hoogleraar, you know that something has gone amiss.

This is a great blog, Henrike, thanks for writing it!

See also the blog on women in high places of colleague Naomi Ellemers at LeidenPsychologyBlog: http://www.leidenpsychologyblog.nl/articles/women-in-high-places

Add a comment