Mummies and coffins in Leiden

Somehow mummies and coffins have always fascinated people. Why? From the moment archaeologists excavated many of them, mummies and coffins started lives that were not originally intended.

Mummies and Coffins in Leiden

On Saturday 14 September 1861, the brothers Edmund and Jules de Goncourt visited the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (National Museum of Antiquities) in Leiden. In their famous diary (in which they critically review the French literary scene of the mid-nineteenth century) they briefly describe their visit to the museum: ‘Looking at unpacked mummies, two mummies of children, I think about the homesickness of those poor containers of the soul, who have been banished from their graves after their death, banished from their homeland, and are now looking at a Dutch canal, dead leaves on the water, a grey sky, a yellowish sun, dark stones and dark trees. It seems to me there is something unnatural, something Godless, in exhibiting mummies against the background of a painting by Pieter de Hooch.’ (Translation mine.)

In other words, they think it is not correct to keep Egyptian mummies in an old Dutch town, far from the original context. Even the mummies feel homesick. The De Goncourts have a point. Why do we collect objects, including human remains, and store and exhibit them to be gazed at by museum visitors?

I cannot solve this problem in this short text (if it can ever be solved), but I can show that the fascination for mummies and coffins is far from extinct, and is in fact one of the cornerstones of policy making in an Antiquities Museum. An interesting phenomenon for anthropologists.

At the initiative of Dr. Alessia Amenta of the Vatican Museums, the Vatican Coffin Project intends to bring together collections and information related to one particular site in Egypt: Bab el-Gasus (Door of the Priests). The site was discovered in 1891 by the Egyptian Mohammed Abd el-Rasul, who duly reported it to the Archaeological Service of his country. The director, the French Egyptologist Eugène Grébaut, immediately started a search. Which led to a spectacular find: 153 mummies in their coffins were found. However, since there was always the risk of looting the tomb had to be emptied very quickly. In eight days all coffins were taken out and transported to Cairo. A considerable number were probably damaged during this ‘rescue’ operation, mummies were lost, and sometimes coffins fell apart. The Egyptian authorities did not know what to do with so many coffins and decided to give them to countries and museums abroad. The Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden received four sets. The museum’s director and influential Egyptologist, Willem Pleyte, could certainly be satisfied.

Both the Museum and the University in Leiden have strong traditions in Egyptological research. Nowadays, a leading academic in the study of mummy coffins is dr. René van Walsem, museum curator Prof. Maarten Raven published on the mummies of the RMO collection (2005), and Dr. Christian Greco is now leading the Leiden section of the Vatican Coffin project. Bab el-Gasus continues to galvanize people into action more than a hundred years after its discovery. The coffins of the museum in Leiden, in the Vatican, and in Paris (the Louvre) are being extensively researched and their life histories, before and after the discovery in 1891, will be described in detail. None of the 153 mummies have ‘survived’ , but the coffins will be restored and shown in exhibitions all over Europe and beyond. At the moment part of the restoration process of the Leiden coffins can be observed by museum visitors in a special exhibition on the Bab el-Gasus research.

The fascination with mummies and coffins appears to be unlimited. Maybe we want to be part of that eternal life that ancient Egyptians seem to have. From the fact that the number of museum visitors always rises when special attention is given to mummies, we can conclude that the agency (see Gell 1998) of a mummy indeed is eternal - probably in a different way than intended by the ancient Egyptians, but mummies are excellent examples of agencies that ‘work’. In 1861, the De Goncourt brothers felt uncomfortable in the Leiden museum, so close to the mummies. In 2013, we find similar feelings among visitors. People are impressed and sometimes become emotional. A visit to the mummy storeroom of the museum is particularly disturbing. I have experienced that several times with visitors. Some people immediately want to leave the storeroom again, after being confronted to so many mummies and their coffins. Apparently, the power of these objects is so overwhelming that they still (after many centuries) strongly influence people who come nearby.

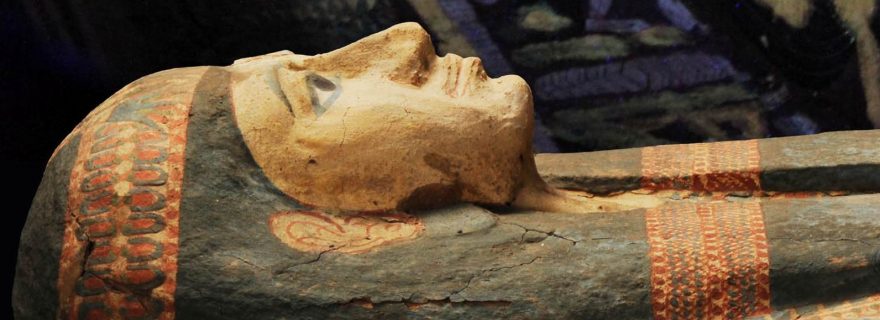

-taoey_AND_Gaoetsesjen.jpg)

Photos: coffins of Nesy-ta-neb(et)-taoey (left) and Gaoetsesjen. By Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

For more information on the Vatican Coffin Project:

- Edmund and Jules de Goncourt, Journal. Mémoires de la Vie Littéraire. Paris: Fasquelle-Flammarion, 1956.

- Alfred Gell, Art and Agency. An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

- Christian Greco et. all., De Reis van de Kisten. Mummiekisten van de Amon-Priesters. Leiden: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, 2013.

- Maarten Raven, Egyptian Mummies. Turnhout: Brepols and the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, 2005

Tip: a lecture on 11 June 2013 in the RMO (in Dutch) is dedicated to this subject: 'De mummiekisten van de Amon-priesters'.

2 Comments

Good news: At least 60 mummies or 'human remains' have 'survived' from Bab el-Gasus.

You write "None of the 153 mummies have survived". How do you know that?

Thank you

Alain

Add a comment