‘Walls of Peace’ and memories of conflict in Belfast

Peace-building by building walls? In Belfast, the capital of Northern Ireland, guided tours to a 3-kilometer-long wall have become a ‘must do’ on the tourist’s schedule. The memorial wall reveals the slow process of reconciliation.

Learning about a conflicting past

Separating a protestant neighbourhood from a Catholic neighbourhood and an industrial complex on the other side of the street, the 15-meter-high wall is just one of the 100 ‘defensive security barriers’ in the city. The texts and paintings on the lower part of the wall can be read as the expression of conflicting and contrasting views on the past, the present, and the future of Belfast and other places in the world.

A group of 25 3rd-year Honours students of our Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences paid a 5-day visit to learn more about peace-building in this city primarily known by many as a place of decades of violent conflict. The visit included lectures at various bodies – such as a political party, the City Council, a community centre, and the Institute of Irish Studies of Queen’s University; there were walks around the city and research activities; and the students were able to watch 2 parades and interact with participants in the parades, spectators, and alert police officers. The first parade was a small daily parade of one of the branches of the Unionists. The second one was the large ‘People’s Parade’ of the Republicans on the Falls Road, commemorating the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916. The Easter Rising marked the proclamation of the Irish Republic and led to a confrontation with the British army and the death of many people, who are now considered national heroes.

Visitors to a ‘wall of peace’. Many of them add new messages.

Building trust and identity

Since the so-called Good Friday Agreement of 1998, signed after a cease fire, the violent conflict between Catholics and Protestants that made Northern Ireland a daily feature in the news, has been reduced. Before and after this agreement, numerous walls were erected to segregate the communities from each other. The labelling of these walls as ‘walls of peace’ is of course quite remarkable, as they merely keep communities apart. Peace-building is not just building walls. On the contrary, many people argue that for real peace the walls would have to be removed to allow interaction between the communities. This however is a long and difficult process, which involves building trust and reducing feelings of hostility and revenge. The process also includes policy domains like the still heavily segregated education system, social housing, and new and inclusive identity building.

A mural of King William III (of Orange), celebrating the victory of the Battle of Boyne.

National and international solidarity

The violent history of Belfast can be read on the numerous murals found all over the city, but in particular in the old Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods. Initially the murals were a mode of expression of the Unionists, celebrating the victory of King William III (of Orange) at the Battle of Boyne in 1690. Together with flags and banners, they were meant to suppress nationalist Irish symbolic displays. This changed in the 1960s, however, when the Catholics’ campaigns for civil rights led to clashes with the police and later the British army.

A mural of Bobby Sands, one of the Republican victims who died in prison after a hunger strike.

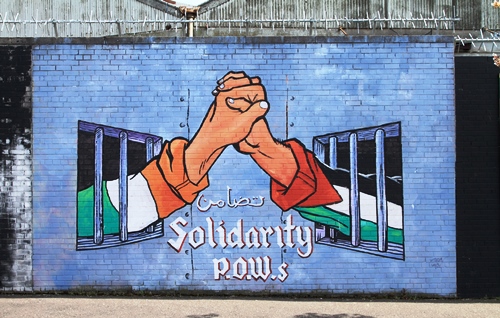

Murals sometimes depict the militant and hostile atmosphere of that time. Many of them also refer to the killing of individual people on both sides. In addition there are expressions of solidarity with groups whose civil rights have been violated, such as allusions to the struggles in South Africa and the PLO. The murals’ references to support groups from the Irish diaspora in Australia and the United States are an indication that the conflict in Northern Ireland had links far beyond the national boundaries.

Solidarity between prisoners of war of the IRA and PLO.

Stimulating Belfast pride

The City Council of Belfast has made serious efforts to reduce the violent and hostile messages of numerous murals by repainting the walls with more positive and future-oriented images. This is done in close collaboration with community workers in the Protestant and Catholic neighborhoods. The council has also commissioned artists to decorate the wall with creative expressions. On some walls one can find the names and faces of famous football players or singers who originate from Northern Ireland, such as George Best and Van Morrison. Or brand names such as Bushmills whiskey. These are meant to stimulate a sense of pride and unity among all the residents of the city.

Industrial style and selfies

In other ways, too, the city of Belfast is trying to overcome what is referred to as ‘dark’ or ‘negative tourism’ focusing on the decades of conflict. The city, with substantial amounts of money from London and Brussels, is rebuilding the city centre and restoring the old housing and industrial complexes, many of which are built in the Victorian architectural style. One of the projects has been the creation of the largest tourist attraction devoted to the Titanic, the ship that was built in Belfast in 1912. With the slogan ‘She was alright when she left here!’, the theme park aims to glorify the achievements of the large work force and industrial achievements of the city at the beginning of the 20th century. It is the number 1 tourist attraction in Northern Ireland.

A mural for the workers who built the Titanic.

Another remarkable new object in the city centre is ‘The Big Fish’, an art project funded by the EU. It is a 10-meter-long salmon covered with fragments of Belfast’s history in the form of photos and texts printed on shining tiles. It symbolises the renovation of the inner city’s quays and the restoration of a healthy environment in the city’s main river, the Lagan. The Big Fish has become the favourite background for selfies ‘made in Belfast’.

The group of honours students in front of The Big Fish.

War of flags

The research question the students had formulated for the visit focused on the process of peace building. In order to find answers to this question they had to interview people and ‘read the urban landscape’, including posters, billboards, murals, memorials, and flags. At the moment the city is also full of election posters. Sometimes they contain messages that are rather straightforward, but others are more difficult to understand. In particular, it is quite a challenge to read the symbolic message of flags in a correct manner, as many flags bear symbols that are not obvious for new visitors to interpret.

In a fascinating lecture Dominic Bryan of the Institute of Irish Studies explained how, to some extent, there is a ‘war of flags’ going on. Probably Northern Ireland has the highest number of legal provisions to reduce the awakening of hostilities by displaying flags and banners in public spaces. These regulations are extremely important in relation to the more than 3,000 parades that are organized in Northern Ireland every year and which take place under strict police surveillance. There is one spot in the city where such a parade takes place every day of the week except Sunday. For years already the parade has been stopped at the end of a street by a heavy police cordon in order to prevent the parade from marching into a street where Catholics live. After exactly one hour the parade is over, and the police and the parade leaders and their followers retreat silently.

A daily parade by the Unionists is stopped by a police cordon.

Hearing the unheard voices

Recently the Belfast City Council’s Good Relations Unit has organised discussions to try to find out how ‘the silent majority’ feel about the parades and protests that often cause tension between the city’s two main traditions. The outcome of the research was to bring out the unheard voice that might provide decision-makers with relevant information on these complex issues. Many of these unheard voices call for more inclusive and less dividing celebrations. Building real peace in Belfast is still very much work-in- (slow)-progress.

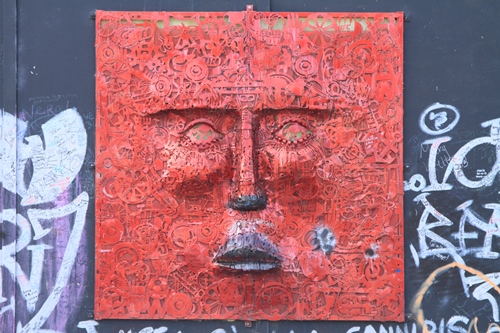

Art work on one of the ‘walls of peace’.

1 Comment

Hoi Gerard,

erg bijzonder te lezen dat de studenten nu naar Noord Ierland gaan !. Ik heb heel wat familie daar wonen, daar m'n moeder er vandaan kwam. Vele jaren jaarlijks op bezoek geweest - tot mijn grootmoeder overleed. nu ga ik nog een enkele keer naar neven en nichten.

de situatie was altijd heel moeilijk in Nederland uit te leggen !

Add a comment