Why reading novels benefits ethnographic writing

These days I mostly spend writing. On the precious moments that I manage to liberate myself from my laptop, I devour novels. Below some reflections on how reading fiction helps me improve my own anthropological writing (...and means to distract myself).

To a selected few, I assume, writing is a wholly joyful activity. Unfortunately, not to me – my attitude is ambivalent, cherishing it one moment and cursing it another. By and large, my days consist of feverishly typing out paragraphs and sections, of reading these back somewhat later blushing with shame, of wailing ‘why, why, why?!?’ in colleagues’ offices, and of convincing myself that the polished books we find in bookshops cannot but be the result of similarly painstaking processes.

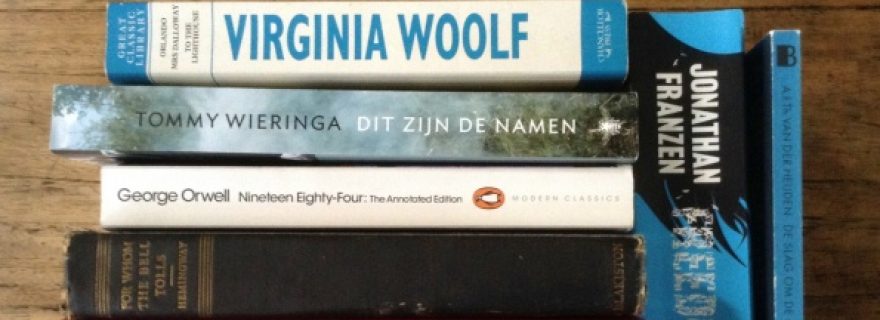

My desk appears to have been forcefully annexed by hordes of books demanding attention, stacks of scribbled-down notes and a squadron of abandoned coffee mugs – it probably looks like pandemonium to an outsider, but it is a well-organized and purposeful chaos to me. Obviously, many of the books and articles on my desk are scholarly works. Yet, among them is usually also a novel. I believe that reading different kind of writings stimulates my creativity, and I often find inspiration in books that have little to do with my professional interests.

Some examples – last week I finished Tommy Wieringa’s latest novel, Dit Zijn de Namen (2012). Here it was not so much the plot, but the technique that excited me. The sentences are kept short, always to the point and functional, but never shallow. As I have a tendency towards overly long sentences myself, full of confusing adjectives, Dit Zijn de Namen has been an eye-opener to me. When desperation lurks I read a page or two, try to catch the rhythm, and return to my own Frankenstein-type-of-words.

Or take Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925). Here, Clarissa is followed over the course of one day, while she prepares for a party in the evening. Such a concept is perhaps not very innovative, yet insightful – I take it as an inspiring exercise in how to build an entire storyline around one particular event. Moving back and forth in time, Mrs. Dalloway could almost be seen as written like an ethnographic present, set against larger historical developments.

In a very different way, I value George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) (last year the sales of the book rocketed after Edward Snowden’s public appearance – I am lured into a sarcastic sneer on this, but since I myself only recently read it I am not the right person to sneer). Again it wasn’t the plot. In fact, I have difficulties with the totalitarian mode of governance it suggests, which has been carefully crafted so as to invade even the smallest corners of society while eradicating all potential for individual agency. However, and even though it has long been part of anthropological common sense to perceive the use of language and the writing of history as inherently political affairs, I did appreciate the minute descriptions of Newspeak and the Ministry of Truth.

I also took great pleasure in Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom (2010), which offers a critical view on contemporary American society. I definitely do not always agree with Franzen, but his style of interweaving personal experiences and wider societal and political developments is almost addictive (and very amusing – particularly the passages on one family member’s involvement with the American NGO The Nature Conservancy I found at times hilarious).

In short, these days I grapple with my data, I try to make sense of snippets of conversations and observations (a.k.a. trying to figure out a bigger picture, presuming there is one), and I rack my brains over structure. All the while, in novels I find the inspiration to take the process of writing itself seriously – good novels teach me to become conscious of my style, and they motivate me to try and write as clearly and effectively as I can.

Finally, in an attempt to retain a certain degree of sanity in the midst of maddening cycles of writing and rewriting, I have found refuge in self-imposed rules and regulations. Most reflect the basic advice you find in any writing guide – don’t trick yourself into thinking that you need ‘inspiration’, writing is mostly discipline and routine. Write every day, so as to not lose touch with your text; take regular breaks, but not too long, and don’t get too distracted. But by having a good yet unfinished novel on my desk, yearning to be read, I always have a valid excuse at hand to avoid this strict regime a bit – if only just for a little while.

4 Comments

hi Marlous,

I am glad to stop by your blog, the term anthropology triggered my interest in writing this to you. I am from India, I want to know what exactly a reader of the novel can elicit intrerms of Anthroplogy? In the sense what to study, is it ehnicity, culture, their traditions, festivals...? or Historical ascent or journey to till date that is portrayed in their works. Awaiting your inputs on this...

Cheers

Satheeshraju

Thank you Laura, for your suggestions.

And indeed - happy reading, everyone!

I totally agree that reading novels can make one a better ethnographer. Two novels I've read recently that informed my thinking and writing were Anthony Marra's amazing first book, A Constellation of Vital Phenomena (about Chechnya), and Smith Henderson's Fourth of July Creek (about the U.S.).

Happy reading, everyone

If, after reading this blog, you have become enthusiastic about reflecting on style and narrative more consciously, you might want to check out Kirin Narayan's 'Alive in the Writing: Crafting Ethnography in the Company of Chekhov' (2012). (http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo10267375.html).

Inspired by this great novelist, Narayan offers a range of practical suggestions on how to create solid and convincing ethnography, by writing creatively and vividly.

Add a comment